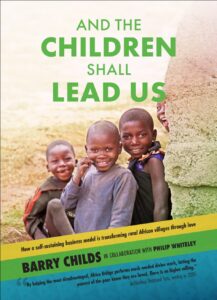

Africa Bridge announces the publication of And The Children Shall Lead Us by Barry Childs – a heartfelt and fascinating account of 23 years of Africa Bridge, the sustainable, cooperative agricultural model transforming rural villages.

This book is published to share the success of the Africa Bridge model – based on both field experience and academic research – and to raise awareness of its powerful potential to lift the most vulnerable children out of poverty.

And The Children Shall Lead Us tells the engrossing story of how the project works, how it came about and was implemented, and what has been learned during its 23 years of operation. This work is not simply “charity”; it’s a proven community-led model that could redefine ethical development in Africa. The book is destined to become recommended reading for the social sciences.

Barry Childs is the founder of Africa Bridge. He spent his childhood in Tanzania and returned later in life to commit himself to helping his homeland. Passionate about the project, Barry has stories to tell. Contact Africa Bridge at [email protected] if you would like to learn more about the book and to schedule a speaking event.

What they say about Africa Bridge:

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, writing in 2005

‘I was moved when Barry Childs spoke to me some years ago of his dream to help children orphaned by HIV/AIDS and their families in Tanzania. By helping the most disadvantaged, Africa Bridge performs much needed divine work, letting the poorest of the poor know they are loved. There is no higher calling.’

Dr Heath Prince, PhD Director, Ray Marshall Center, University of Texas at Austin and Senior Development Economist at La Isla Network

‘Africa Bridge does what precious few other programs have managed to do – it lifts children out of poverty, allowing them to tap into their full potential, and setting them on a course to break the inter-generational cycles of poverty that have robbed them and their communities of the opportunity to live lives of their own choosing, rather than those determined by privation. Founded on love, ingenuity, and dedication, Africa Bridge’s impressive success gives the lie to the lazy assertions that the problem of poverty is unsolvable.’

Paperback and eBooks are Available for preorder on Amazon, with eBooks also on Kobo. To order from bookshops, (ISBN 9781739379377). Expect a delivery date of April 8, 2024. Price for the eBook is $8.99, and the paperback is $18.

PS. Springwater Trails supporters can give a small extra boast to Barry’s project by using the preorder option on Amazon or at your book store. This helps to make April 8 an extra successful sales day.